SHORT

BIOGRAPHY

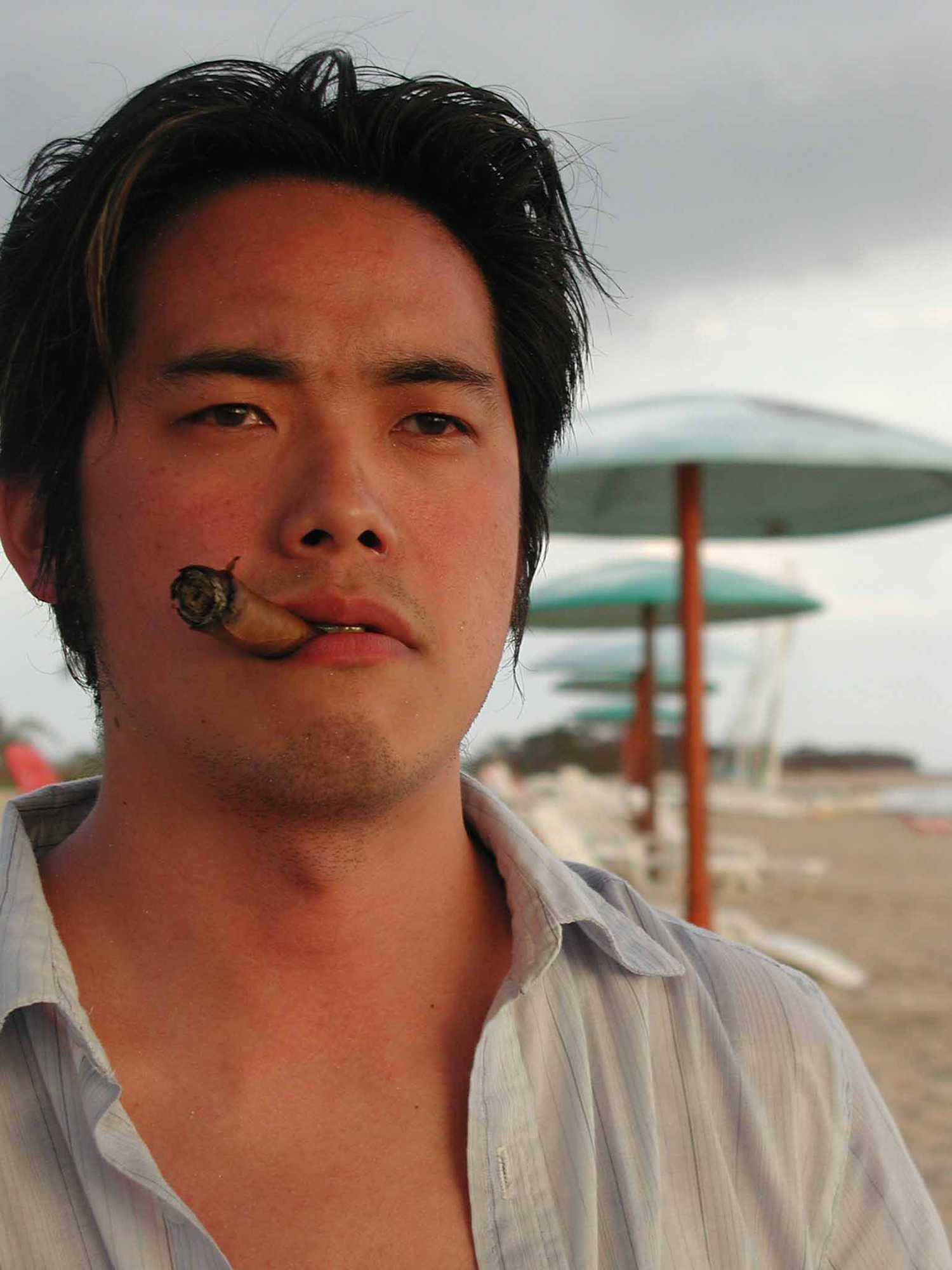

A recipient of the Rome Prize and the Berlin Prize, Ken Ueno (b. 1970), is a composer/vocalist/sound artist who is currently a Professor at UC Berkeley, where he holds the Jerry and Evelyn Hemmings Chambers Distinguished Professor Chair in Music. Ensembles and performers who have played Ken’s music include Kim Kashkashian and Robyn Schulkowsky, Mayumi Miyata, Teodoro Anzellotti, Aki Takahashi, Wendy Richman, Greg Oakes, BMOP, Alarm Will Sound, Steve Schick and the San Francisco Contemporary Music Players, the Nieuw Ensemble, and Frances-Marie Uitti. His music has been performed at such venues as Lincoln Center, the Kennedy Center, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, MusikTriennale Köln Festival, the Muziekgebouw, Ars Musica, Warsaw Autumn, Other Minds, the Hopkins Center, Spoleto USA, Steim, and at the Norfolk Music Festival. Ken’s piece for the Hilliard Ensemble, Shiroi Ishi, was featured in their repertoire for over ten years, with performances at such venues as Queen Elizabeth Hall in England, the Vienna Konzerthaus, and was aired on Italian national radio, RAI 3. Another work, Pharmakon, was performed dozens of times nationally by Eighth Blackbird during their 2001-2003 seasons. A portrait concert of Ken’s was featured on MaerzMusik in Berlin in 2011. In 2012, he was a featured artist on Other Minds 17. In 2014, Frances-Mairie Uitti and the Boston Modern Orchestra premiered his concerto for two-bow cello and orchestra, and Guerilla Opera premiered a run of his chamber opera, Gallo, to critical acclaim. He has performed as soloist in his vocal concerto with the Boston Modern Orchestra Project in New York and Boston, the Warsaw Philharmonic, the Lithuanian National Symphony, the Thailand Philharmonic Orchestra, and with orchestras in North Carolina, Pittsburgh, and California. Ken holds a Ph.D. from Harvard University. A monograph CD of three orchestral concertos was released on the Bmop/sound label. His bio appears in The Grove Dictionary of American Music.

FULL

BIOGRAPHY

Ken Ueno (b. 1970), is a composer, vocalist, improviser, and sound artist. His music celebrates artistic possibilities which are liberated through a Whitmanesque consideration of the embodied practice of unique musical personalities. Much of Ueno’s music is “person-specific” wherein the intricacies of performance practice are brought into focus in the technical achievements of a specific individual fused, inextricably, with that performer’s aura. In an increasingly digitized world, “person-specificity” takes a stand against the forces that render all of us anonymous. It also runs counter to the neo-colonial tradition of transportability in Western Classical music. As an outsider, Ueno has been drawn to sounds that have been overlooked or denied. His artistic mission is to push the boundaries of perception and challenge traditional paradigms of beauty.

Breath is at the ontological center of Ueno’s art practice as a vocalist specializing in extended techniques (overtones, throat-singing, multiphonics, extreme registers, circular singing), and taking a cue from Robert Hass’ thesis that “poetry is: a physical structure of the actual breath of a given emotion,” his practice transposes this notion into music through physical valence. Ueno believes that physical gestures are, indeed, mapped to given emotions. When we hear the operatic tenor, Pavarotti, sing a high C and linger there for tens of seconds, he not only suspends his breath, but, we, too, as listeners, suspend our breath. Physio-valence directs our bodies to vivify, in real time, the suspension of our breath in parallel with the music to which we are listening. In his music, through circular breathing, that Pavarottian lingering moment is expanded to minutes, not seconds. The phenomenological reading of that lingering exacerbates traditional modes of analysis in terms of structural hearing.

Ken Ueno performing

‘TARD at MATA 2018 with

Du Yun, Matt Evans, and

Amy Garapic.

More Info

(LINK︎︎︎)

‘TARD at MATA 2018 with

Du Yun, Matt Evans, and

Amy Garapic.

More Info

(LINK︎︎︎)

Ueno employs the megaphone as a prosthetic extension of his voice. Armed with a megaphone, he is mobile and able to incorporate the narrative of movement in space, direct his sound in different directions, at different structural materials and angles, and to play with various lengths of echoes. And articulating the resonant frequencies of different locations in a space, means that architecture, too, can be read as harmonic structure (in this way, Ueno’s music sonically articulates architecture – in his installations, he “instrumentalizes” architecture). Ueno has developed an array of vocal techniques specific to the megaphone. For example, a kind of slap tongue whose attack is followed by a multiphonic drone shaped by changing the vowel shapes within his mouth. The shapes of these bespoke vowels, however, do not exist in any language. He has also learned to control the aperture of the multiphonic (or bandwidth) with the shape of his mouth, and can also sing in counterpoint or in augmentation with the shaped feedback multiphonic by humming into his nasal cavity. There are other techniques which involve ingressive singing, which, in alternation with exhaled techniques, allows me to circular-breathe.

Ensembles and performers who have played Ueno’s music include Kim Kashkashian and Robyn Schulkowsky, Frances-Marie Uitti, Mayumi Miyata, Teodoro Anzellotti, Aki Takahashi, Alarm Will Sound, the Boston Modern Orchestra Project, Steve Schick and the San Francisco Contemporary Music Players, Wendy Richman, Greg Oakes, Gabby Diaz, Anne Lanzilotti, Vincent Daoud, Karen Yu, Dan Lippel, Aaron Larget-Caplan, Sound Icon, Alia Musica Pittsburgh, the Warsaw Philharmonic, the Lithuanian National Symphony, the Paul Dresher Ensemble (with Amy X Neuburg), the Nieuw Ensemble, Neue Vocalisolisten, , the Del Sol String Quartet, Vincent Royer, the Bang on a Can All-Stars, the American Composers Orchestra (Whitaker Reading Session), the Cassatt Quartet, the New York New Music Ensemble, the Prism Saxophone Quartet, the Atlas Ensemble, Relâche, the Pro Arte Chamber Orchestra, Dogs of Desire, the Orkest de Ereprijs, and the So Percussion Ensemble.

ALIANA DE LA GUARDIA,

LEFT, AND DOUGLAS DODSON

IN THE GUERILLA OPERA

PRODUCTION OF KEN UENO’S

CHAMBER OPERA GALLO.

(PHOTO: LIZ LINDER)

MORE INFO

(LINK︎︎︎)

Ueno’s music has been performed at prestigious venues around the world including Lincoln Center, the Kennedy Center, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, MusikTriennale Köln Festival, Ars Musica, Warsaw Autumn, the GAIDA festival, Darmstädter Ferienkurse, the Muziekgebouw, the Hopkins Center, Spoleto USA, and Steim. He has been the featured guest composer at the Takefu International Music Festival, the Norfolk Music Festival, the Great Lakes Chamber Music Festival, the Pacific Rim Festival, the Intégrales New Music Festival, and the MANCA Festival. Ueno’s piece for the Hilliard Ensemble, Shiroi Ishi, was featured in their repertoire for over ten years, with performances at such venues as Queen Elizabeth Hall in England, the Vienna Konzerthaus, and was aired on Italian national radio, RAI 3. Another work, Pharmakon, was performed dozens of times nationally by Eighth Blackbird during their 2001-2003 seasons. A portrait concert of Ueno’s was featured on MaerzMusik in Berlin in 2011. In 2012, he was a featured artist on Other Minds 17. In 2014, Frances-Mairie Uitti and the Boston Modern Orchestra premiered his concerto for two-bow cello and orchestra this past January, and Guerilla Opera premiered a run of his chamber opera, Gallo, to critical acclaim. He has performed as soloist in his vocal concerto with the Boston Modern Orchestra Project in New York and Boston, the Warsaw Philharmonic, the Lithuanian National Symphony, the Thailand Philharmonic Orchestra, and with orchestras in North Carolina, California, Stony Brook, and Pittsburgh. During two weeks in the fall of 2019, he was in residence at the Osage Gallery in Hong Kong to present installations, installations performances, concerts, and take part in a panel discussion on his works at Hong Kong University. He also curated a team of local stars with whom he performed at Osage.

Awards, grants, and fellowships that Ueno has received include those from the American Academy in Rome, the American Academy in Berlin, Civitella Rainieri, the Townsend Center, the Mellon Foundation, the Fromm Music Foundation (2), New Music USA (4), the Pittsburgh Foundation, the Aaron Copland House, the Aaron Copland Fund for Music Recording, Meet the Composer (6), the National Endowment for the Arts, the Belgian-American Education Foundation, and Harvard University. He has twice received support from the Fromm Foundation to support orchestral commissions. He has also received support from the MAP Fund twice – for an evening-long work for Community MusicWorks and himself as vocalist, and for a work for the combined forces of the Prism Saxophone Quartet and the Partch Ensemble. A monograph CD of three of his concertos was released on the Bmop/sound label. In the Spring of 2017, he was a Mellon Visiting Artist at the Susan and Donald Newhouse Center for the Humanities at Wellesley College.

As a vocalist/improviser, Ueno has collaborated with Ryuichi Sakamoto, Joey Baron, Ikue Mori, Robyn Schulkowsky, Joan Jeanrenaud, Pascal Contet, Gene Coleman, Tyshawn Sorey, David Wessel, Robin Hayward, John Kelly, Jorrit Dykstra, Kevork Mourad, Gilberto Bernardes, Hans Tutschku, James Coleman, and Vic Rawlings amongst others. Ueno’s ongoing performance projects include collaborations with DJ Sniff, Kung Chi Shing, Tim Feeney, Matt Ingalls, and Du Yun.

As a sound artist, Ueno collaborates with visual artists, architects, and video artists to create unique cross-disciplinary art works. For the artist, Angela Bulloch, he created several audio installations (driven with custom software), which provide audio input that affect the way her mechanical drawing machine sculptures draw. These works have been exhibited at Art Basel as well as at Angela’s solo exhibition at the Wolfsburg Castle. In collaborating with the architect, Patrick Tighe, Ueno created a custom software-driven 8-channel sound installation that provided the sonic environment for Tighe’s robotically carved foam construction. Working with the landscape architect, Jose Parral, he collaborated on videos, interactive video installations, and a multi-room intervention at the art space Rialto, in Rome, Italy. In 2013, Ueno created a 24-channel audio installation, Liquid Lucretius, which was installed at the Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo in Mexico City for two months. Breath Cloud, a sound installation with 90-speakers was commissioned and installed at the Taipei Fine Arts Museum in May, 2014. 2014 also saw the opening of his collaboration with the architect, Thomas Tsang, at the Inside-Out Museum in Beijing. The software-driven work sonically activates a stairwell as a resonant chamber, which leads to a sonic aperture with an opening outside the building, effectively turning the building into a large wind instrument. More recent sound installations have been commissioned by the RISD Art Museum and the Bi-City Bienniale of Urbanism/Architecture in Shenzhen, China. More recently, he has created installation performances at galleries in Guangzhou, and spaces in Taiwan, and Savannah, GA (commissioned by the Telfair Museum).

Ken collaborated with

architect Patrick Tighe on

Memory Temple, a custom

software-driven sound

installation at SCI-ArC.

(PHOTO: TIGHE ARCHITECTURE)

More Info

(Link︎︎︎)

Ueno is a Professor at the University of California, Berkeley, where he is currently the Jerry and Evelyn Hemmings Chambers Distinguished Professor in Music. He has been invited to present lectures on his music at over a hundred peer institutions, including Harvard, Yale, Cornell, Columbia, Peabody, Stanford, Northwestern, USC, UCLA, Seoul National University, Beijing Central Conservatory, the University of Hong Kong, the Geneva Conservatory, and the Paris Conservatory. He holds a Ph.D. from Harvard University and an M.M.A. from the Yale School of Music, and his bio appears in The Grove Dictionary of American Music.

PRESS

PHOTOS

PHOTO CREDIT

EMPAC/Mick Bello

PHOTO CREDIT

Nanamu Hamamoto

PHOTO CREDIT

Peter Gannushkin

PHOTO CREDIT

Annette Hornischer

PHOTO CREDIT

Thilo Rückeis

The New York Times

(Read︎︎︎)

REVIEW BY

Anastasia Tsioulcas

DATE OF PUBLICATION

Oct. 13, 2022

DESCRIPTION

CRITIC’S PICK

Review: Musicians of Color Reclaim Control in a White Space

“Ueno’s score nods to 19th-century Western idioms, traditional Korean music and shimmering contemporary electronica. The effect is not a pastiche, but a sonic code switching. He also allows Tines and Koh — exemplary technicians and artists of profound intensity — to explore their full tonal and textural ranges. Moments of racial violence are evoked by Koh playing growling, guttural scratch tones, often on her open G string, while Tines cycles from his rich basso profundo to an ethereal falsetto. (The day before “Everything Rises” opened, BAM named Tines as its next artist in residence, beginning in January.)

The piece ends with a hopeful original song, “Better Angels,” which is preceded by a particularly haunting sequence.“

Asia Pacific Arts

(Read︎︎︎)

REVIEW BY

Vania Fong

DATE OF PUBLICATION

April. 25, 2022

DESCRIPTION

The last piece, “Better Angels,” is a simple yet powerful song about embracing “the better angels of our nature” in the face of historical injustices and generations of invisibilization and oppression. In this performance space, grief, sorrow, and guilt arose in response to Tines and Koh’s deeply personal stories, but so did empathy, hope, and admiration for the performers and their families for stepping into the unknown, whether it be a new country or a bold musical statement, in hopes that the next generation can live a better life and “stop singin’ songs for freedom / because in fact [they] are free” (Ueno, “Amen”).

The Wire

(Read︎︎︎)

REVIEW BY

Emily Pothast

DATE OF PUBLICATION

2020 December

DESCRIPTION

“For UC Berkeley music professor and composer Ken Ueno, the bullhorn has become an extension of his extended vocal technique, rooted in circular breathing and throat-singing techniques.”

Wallpaper

(Read︎︎︎)

REVIEW BY

Anna Yudina

DATE OF PUBLICATION

2017 December 28

DESCRIPTION

“Tsang’s own contribution – an immersive installation designed to amplify the soundwork by composer and vocalist Ken Ueno – is one of the exhibition’s highlights that mark the 2017 Biennale’s active involvement with contemporary art.”

The Log

Journal

(Read︎︎︎)

REVIEW BY

Steve Smith

DATE OF PUBLICATION

2017 April 14

DESCRIPTION

“Rollicking and meditative in alternation, the music sustains its initial fascination; Ueno’s techniques are novel, but never mere novelty, serving expressive purposes consistently throughout this haunting work.”

Seen and Heard

International

(Read︎︎︎)

REVIEW BY

Daniele Sahr

DATE OF PUBLICATION

2017 April 7

DESCRIPTION

“Within this eclectic space of exploration (which includes throat singing) he produces songs like There is No One Like You sung by Connery, that you want to add to your soundtrack to reshuffle an evening after work. It is not only testament to his accessibility but also his wide range of musicality that he can touch the tastes of all his listeners.”

NEW YORK TIMES

(Read︎︎︎)

REVIEW BY

Corinna da Fonseca-Wollheim

DATE OF PUBLICATION

2016 June 14

DESCRIPTION

“The rubbery sputter that this exotic-looking instrument now emitted added to the dynamic contrast between organic and inorganic sounds in ‘Future Lilacs.’ The work opens with a dynamic rock-charged section in which the electric guitar worries away at a single note with microtonally altered impulses, then settles into a languid postlude that again makes beautiful use of the ethereal cloud-chamber bowls.”

blogs.

post-gazette.com

(Read︎︎︎)

REVIEW BY

Elizabeth Bloom

DATE OF PUBLICATION

2015 November 13

DESCRIPTION

“The concerto itself was raw, ear-tingling and visceral. Despite thinking that the highest note he could sing was C-Sharp, three octaves above middle C, he in fact hit the D a half-step higher. Quite the memorable evening.”

artsbeat.

blogs.nytimes.com

(Read︎︎︎)

REVIEW BY

Corinna da Fonseca-Wollheim

DATE OF PUBLICATION

2015 October 7

DESCRIPTION

“Ken Ueno’s ‘Peradam’ offers a heady brew of harmonies flickering with microtones, harmonics and vocalizations that draws heavily on the individual talents of the versatile Del Sol players, which in the case of the violist Charlton Lee includes eerily accomplished samples of Tuvan throat singing.”

My Entertainment

World

(Read︎︎︎)

REVIEW BY

Brian Boruta

DATE OF PUBLICATION

2014 June 7

DESCRIPTION

“Gallo is intellectual theatre of the highest order, but, unlike most other theatre of which this is true, it refuses to be up tight, and removes just about every ounce of pretention from the air around it. After all, it’s hard to be pretentious while barefoot, on a beach towel, on a bench, in front of a beach of Cheerios. Yes, Cheerios, the beloved breakfast cereal which serves as both sand and projection screen during Ueno’s 90 minute opera about memory, landscapes, and the shifting tides of what it means to exist and be in this world.”

Boston Musical

Intelligencer

(Read︎︎︎)

REVIEW BY

John Kochevar

DATE OF PUBLICATION

2014 June 2

DESCRIPTION

“Gallo was ultimately compelling in conception and performance. Nature will serve us with more disasters; ‘the present-day composer refuses to die.’”

Boston GLOBE

(Read︎︎︎)

REVIEW BY

Matthew Guerriri

DATE OF PUBLICATION

2014 June 2

DESCRIPTION

“...very much an experimental opera, not only in its willingness to try anything, but in that its dramatic impulse is, in essence, its inventive impulse. Opera might be the only form capable of housing the piece’s superabundance of ideas; Ueno recapitulates a bit of genre phylogeny while demonstrating that the family tree still produces surprising branches.”

Seen and Heard

International

(Read︎︎︎)

REVIEW BY

Daniele Sahr

DATE OF PUBLICATION

2014 January 29

DESCRIPTION

“...a combination of the strange and beautiful, as he blended his voice with the transcendent meditative quality evoked in Peradam.”

NewMusicBox

(Read︎︎︎)

REVIEW BY

Matthew Guerrieri

DATE OF PUBLICATION

2014 January 28

DESCRIPTION

“The ending—a long cadenza which featured Uitti creeping up the fingerboard into a distant, shortwave squeal of high natural harmonics—was breathtaking.”

New York Times

(Read︎︎︎)

REVIEW BY

Corinna da Fonseca-Wollheim

DATE OF PUBLICATION

2013 January 25

DESCRIPTION

“Sometimes they were even gorgeous, as in ‘Shiroi Ishi,’ an a cappella work by Ken Ueno. Mr. Ueno is a composer on the faculty of the University of California, Berkeley, who in his own singing explores and expands the eerie overtones created by techniques like Tuvan throat singing.”

CHICAGO

CLASSICAL REVIEW

(Read︎︎︎)

REVIEW BY

Lawrence A. Johnson

DATE OF PUBLICATION

2012 March 30

DESCRIPTION

“Ken Ueno’s Disjecta turned out to be the most compelling work of the evening.”

NEW YORK TIMES

(Read︎︎︎)

REVIEW BY

Allan Kozinn

DATE OF PUBLICATION

2011 April 13

DESCRIPTION

“‘(X)igagai,’ a gripping, visceral soundscape inspired by the Pirahã people of the Amazon basin, a fascinating tribe whose language apparently has no words for colors or numbers. (The title refers to spirits that only the Pirahã people are able to see.)”

Consequence

of Sound

(Read︎︎︎)

REVIEW BY

Jake Cohen

DATE OF PUBLICATION

2011 April 13

DESCRIPTION

“...matched by the dissonance, experimentalism, and sheer bravado of Ken Ueno’s piece for Alarm Will Sound, (X)igágáí. Ueno’s piece explored different kinds of white noise and wind-like timbres, utilizing a full array of human- and instrument-generated white noise.”

Seated Ovation

(Read︎︎︎)

REVIEW BY

Will Robin

DATE OF PUBLICATION

2011 April 2

DESCRIPTION

“The best piece of the bunch was Two Hands, a placid work for violist Kim Kashkashian and percussionist Robyn Schulkowsky, a success as much for its compositional rigor as for its luminous performance—Kashkashian, the dean of American viola, gave each individual gesture a sense of inevitability, the kind of radiant deliberateness one hears in a great reading of Mozart or Bach.”

Baltimore Sun

(Read︎︎︎)

REVIEW BY

Tim Smith

DATE OF PUBLICATION

2010 December 8

DESCRIPTION

“The finale showed the composer at his most persuasive. ‘Talus’ was written for violist Wendy Richman, who broke her ankle in a fall in 2006 — during a rehearsal for a David Lang opera. Ueno essentially dramatizes that accident — the piece starts with a scream from the soloist — but he avoids gimmicky. It's quite a deep and involving work of exceptional lyrical power with long-sustained notes and the spaces in between. Richman was the impressive player. She had the tense harmonic language communicating vividly.”

American Record

Guide Reviews

Ken Ueno: Talus

(Read︎︎︎)

REVIEW BY

Robert Haskins

DATE OF PUBLICATION

2010 September 1

DESCRIPTION

“Ueno writes strongly against the grain of standard expectations for the concerto by reserving the second half of the piece for the two soloists alone. And what sounds like a simple, almost banal gesture becomes incredibly moving—a daring decision that perfectly matches the poetry of the work. It is completely in keeping with Ken Ueno, who I believe is going to be an extremely important American composer.”

Washington

Post

(Read︎︎︎)

REVIEW BY

Steven Brookes

DATE OF PUBLICATION

2010 September 21

DESCRIPTION

“‘Sabinium’ was fascinating throughout.”

Detroit

Free Press

(Read︎︎︎)

REVIEW BY

Mark Stryker

DATE OF PUBLICATION

2009 June 13

DESCRIPTION

“Ueno relies on fiercely concentrated, pointillistic gestures and unusual effects to evoke a state of suspended meditation: gentle scrapes, quick slashes, erotic shivers, cold stares, fleeting melodies that shimmer like apparitions.”

Boston Globe

(Read︎︎︎)

REVIEW BY

Matthew Guerriri

DATE OF PUBLICATION

2008 November 18

DESCRIPTION

“It’s a concerto that engrossingly reinvents the discourse.”

The Boston Musical

Intelligencer

(Read︎︎︎)

REVIEW BY

Peter Van Zandt Lane

DATE OF PUBLICATION

2008 November 14

DESCRIPTION

“...one cannot deny that Talus was the most memorable piece of the evening.”

Washington

Post

(Read︎︎︎)

REVIEW BY

Stephen Brookes

DATE OF PUBLICATION

2008 April 28

DESCRIPTION

“...the piece had a fascinating, elemental power that resonated long after it ended.”

Sequenza 21

(Read︎︎︎)

REVIEW BY

John Nasukaluk Clare

DATE OF PUBLICATION

2008 April 3

DESCRIPTION

“After intermission, the amazingly creative ‘On a Sufficient Condition for the Existence of Most Specific Hypothesis’ by Ken Ueno was captivating. A natural blend of dissonance and glissandi, along with rough and sudden entrances of instruments, made a perfect parallel to Ueno’s singing... Most impressive was a cadenza-like throat singing passage, including a brilliant range of dynamics and wide intervals. I’ll listen for more Ueno in the future.”

Boston Globe

(Read︎︎︎)

REVIEW BY

Matthew Guerriri

DATE OF PUBLICATION

2008 March 31

DESCRIPTION

“Ken Ueno's absorbing On a Sufficient Condition for the Existence of Most Specific Hypothesis is a concerto for himself, singing, screeching, growling, throat singing - manipulating the growl's acoustic overtones. The opening - a recording of Ueno at the age of 6, babbling - foreshadowed serious play, the complex resonances of Ueno's vocal excursions transformed into bright orchestral fanfares. The work's single-mindedness proved disarmingly generous. It was the evening's far-out highlight.”

mikedidonato.com

(Read︎︎︎)

REVIEW BY

Mike DiDonato

DATE OF PUBLICATION

2008 March 31

DESCRIPTION

“Intermission came and went and the second half started with the music Ken Ueno with yet another world premier. This one called ‘On a Sufficient Condition for the Existence of Most Specific Hypothesis.’

DANG!

Ken is an overtone singer. and I was BLOWN away.”

BOSTON HERALD

(Read︎︎︎)

REVIEW BY

Christine Fernsebner

DATE OF PUBLICATION

2008 March 31

DESCRIPTION

“Ken Ueno also drew a loud reaction, and the greatest variety of reactions, with his first classical throat-singing work.”

Reviews of Concerts in

Boston and at Tufts

(Read︎︎︎)

REVIEW BY

Emily Hoyler

DATE OF PUBLICATION

2008 March 30

DESCRIPTION

“Composer and vocal soloist Ken Ueno offered the audience a rare treat of vocal technique and compositional innovation.”

Brainwashed

(Blood Money,

“Axis of Blood”

Review)

(Read︎︎︎)

REVIEW BY

John Kealy

DATE OF PUBLICATION

2006 July 12

DESCRIPTION

“Ken Ueno's vocals are incredible. He goes from deep, booming growls to high pitched squeals, the kind that I would normally associate with a boiling kettle or Blixa Bargeld. Using circular breathing techniques Ueno keeps his vocals going continuously for large stretches of time (growling on the exhalation, squealing on the inhalation). As well as being physically impressive, it goes well with Whitney and Worster's rhythms and noise.”

Boston Globe

(Read︎︎︎)

REVIEW BY

Kevin Lowenthal

DATE OF PUBLICATION

2005 May 30

DESCRIPTION

“The concert opener, the world premiere of Ueno's ‘Kaze-no-Oka (Hill of the Winds)’ (2005), featured Japanese masters Kifu Mitsuhashi on shakuhachi (bamboo flute) and Yukio Tanaka on biwa (Japanese lute).

The piece began with the orchestra alone. Dense, slowly shifting microtonal sound-masses — earthy rumblings against ethereal chord-clouds — painted a vast, brooding aural landscape.”

NewMusicBox

(Read︎︎︎)

REVIEW BY

Julia Werntz

DATE OF PUBLICATION

2005 July 1

DESCRIPTION

“Many composers might shy away from separating these elements so completely, for fear of incongruity. But the tension at the moment of the duo's entry, the sustained intensity and relatedness of the music despite the sudden drop in density, the surprising length of the cadenza - these things resulted in a piece with its own strong sense of balance and ‘meaning.’”

The Atlanta

Journal-Constitution

(Read︎︎︎)

REVIEW BY

Pierre Ruhe

DATE OF PUBLICATION

2003 November 4

DESCRIPTION

“The evening was redeemed by the last work, ‘...Blood Blossoms...,’ composed last year by Boston-based Ken Ueno, who was in the audience. Funky and asymmetrical, the score is thick with scary tremolos, punctuated by blasts of percussion or piano. It lopes along all crazylike. It was a nifty piece by a young composer worth following and showed the value of BF's mission: bringing to Atlanta vital contemporary music you can't find anywhere else.”

The Boston Phoenix

(Read︎︎︎)

REVIEW BY

Will Spitz

DATE OF PUBLICATION

2005 May 27 - June 2

DESCRIPTION

“Who ever said that practice makes perfect? UMass-Dartmouth professors Jorrit Dijkstra and Ken Ueno didn't even bother to rehearse for their debut as an improvised duo last Friday at the NAO Gallery in SoWa.“

Press

Reviews/ARTICLES

The New York Times

Publication

Oct. 13, 2022

REVIEW BY

Anastasia Tsioulcas

Originally published

in Publication

(Link︎︎︎)

Not long

into “Everything Rises,” which opened at the Brooklyn Academy of Music on

Wednesday night, the bass-baritone Davóne Tines confronts the audience with an

uncomfortable declaration.

“I was the moth, lured by your flame,” Tines, who is Black, sings with disdain. “I hated myself for needing you, dear white people: money, access and fame.”

“Everything Rises” is a timely collaboration, created by the Korean American violinist Jennifer Koh and Tines, that interrogates what it means to be a classical musician of color — to have chosen to make a creative life and professional career in a medium and a milieu that are overwhelmingly white, and to have tucked away fundamental elements of their identities in the process. The result of those inquiries is a compact, affecting and meditative multimedia work made entirely by people of color, including the composer and librettist Ken Ueno, the director Alexander Gedeon and the dramaturg Kee-Yoon Nahm.

Koh and Tines conceived this show several years ago. Its debut was originally scheduled for spring 2020, but because of the pandemic it instead premiered this April at the University of California, Santa Barbara. What happened across the United States between those two dates — particularly in terms of racial violence perpetrated against Black and Asian Americans — made the enterprise seem even more pressing.

The work begins with Koh and Tines dressed in typical concert dress: she in a wine-colored gown, crowned with demure dark hair, and he in a tuxedo. But he is also wearing a black blindfold, which leaves him feeling his way across the expanse of the Fishman Space stage at BAM. Early on, the audience sees a video clip of Koh’s winning performance as a 17-year-old at the 1994 Tchaikovsky competition in Moscow, an early highlight of what could have been a traditional career.

Soon enough, however, Koh reveals her true, hot pink hair. Tines puts his customary earrings on. The duo wear fitted black tank tops with voluminous black skirts — a coming into their full selves, and a recognition of the parallels of their individual paths.

Musically and narratively, “Everything Rises” underlines the fact that Koh and Tines, as well as their creative partners, are constantly code switching, depending on where they are and whom they are with. Ueno imaginatively expresses those frequent alternations between ways of being, drawing texts from their experiences and sampling audio recordings of interviews with the matriarchs of their respective families: Koh’s mother, Gertrude Soonja Lee Koh, who fled the Korean War to the U.S., and Tines’s grandmother, Alma Lee Gibbs Tines, a descendant of enslaved people.

Ueno weaves clips of these women recounting chilling, graphic stories. Alma recalls the lynching of one of her relatives — “they killed him and hung him, cut his head off and they kicked his head down the streets” — while Soonja remembers, “I saw people being tortured and people on the trees, bodies hanging on the trees.”

There are also moments of melancholic tenderness in “Everything Rises,” such as in the lullaby-like “Fluttering Heart,” and testaments to enduring resilience. Over the course of the show, Tines and Koh hold each other up literally and figuratively: hearing, acknowledging and amplifying each other’s stories.

Ueno’s score nods to 19th-century Western idioms, traditional Korean music and shimmering contemporary electronica. The effect is not a pastiche, but a sonic code switching. He also allows Tines and Koh — exemplary technicians and artists of profound intensity — to explore their full tonal and textural ranges. Moments of racial violence are evoked by Koh playing growling, guttural scratch tones, often on her open G string, while Tines cycles from his rich basso profundo to an ethereal falsetto. (The day before “Everything Rises” opened, BAM named Tines as its next artist in residence, beginning in January.)

The piece ends with a hopeful original song, “Better Angels,” which is preceded by a particularly haunting sequence. Ueno writes a new setting of “Strange Fruit,” the powerful song, made famous by Billie Holiday, that portrays violence against Black Americans and that, in part, led to Holiday’s prosecution by the U.S. government. It’s impossible not to imagine Holiday’s ancestral shadow as part of this work: Alongside Alma and Soonja, she becomes its third matriarch.

“I was the moth, lured by your flame,” Tines, who is Black, sings with disdain. “I hated myself for needing you, dear white people: money, access and fame.”

“Everything Rises” is a timely collaboration, created by the Korean American violinist Jennifer Koh and Tines, that interrogates what it means to be a classical musician of color — to have chosen to make a creative life and professional career in a medium and a milieu that are overwhelmingly white, and to have tucked away fundamental elements of their identities in the process. The result of those inquiries is a compact, affecting and meditative multimedia work made entirely by people of color, including the composer and librettist Ken Ueno, the director Alexander Gedeon and the dramaturg Kee-Yoon Nahm.

Koh and Tines conceived this show several years ago. Its debut was originally scheduled for spring 2020, but because of the pandemic it instead premiered this April at the University of California, Santa Barbara. What happened across the United States between those two dates — particularly in terms of racial violence perpetrated against Black and Asian Americans — made the enterprise seem even more pressing.

The work begins with Koh and Tines dressed in typical concert dress: she in a wine-colored gown, crowned with demure dark hair, and he in a tuxedo. But he is also wearing a black blindfold, which leaves him feeling his way across the expanse of the Fishman Space stage at BAM. Early on, the audience sees a video clip of Koh’s winning performance as a 17-year-old at the 1994 Tchaikovsky competition in Moscow, an early highlight of what could have been a traditional career.

Soon enough, however, Koh reveals her true, hot pink hair. Tines puts his customary earrings on. The duo wear fitted black tank tops with voluminous black skirts — a coming into their full selves, and a recognition of the parallels of their individual paths.

Musically and narratively, “Everything Rises” underlines the fact that Koh and Tines, as well as their creative partners, are constantly code switching, depending on where they are and whom they are with. Ueno imaginatively expresses those frequent alternations between ways of being, drawing texts from their experiences and sampling audio recordings of interviews with the matriarchs of their respective families: Koh’s mother, Gertrude Soonja Lee Koh, who fled the Korean War to the U.S., and Tines’s grandmother, Alma Lee Gibbs Tines, a descendant of enslaved people.

Ueno weaves clips of these women recounting chilling, graphic stories. Alma recalls the lynching of one of her relatives — “they killed him and hung him, cut his head off and they kicked his head down the streets” — while Soonja remembers, “I saw people being tortured and people on the trees, bodies hanging on the trees.”

There are also moments of melancholic tenderness in “Everything Rises,” such as in the lullaby-like “Fluttering Heart,” and testaments to enduring resilience. Over the course of the show, Tines and Koh hold each other up literally and figuratively: hearing, acknowledging and amplifying each other’s stories.

Ueno’s score nods to 19th-century Western idioms, traditional Korean music and shimmering contemporary electronica. The effect is not a pastiche, but a sonic code switching. He also allows Tines and Koh — exemplary technicians and artists of profound intensity — to explore their full tonal and textural ranges. Moments of racial violence are evoked by Koh playing growling, guttural scratch tones, often on her open G string, while Tines cycles from his rich basso profundo to an ethereal falsetto. (The day before “Everything Rises” opened, BAM named Tines as its next artist in residence, beginning in January.)

The piece ends with a hopeful original song, “Better Angels,” which is preceded by a particularly haunting sequence. Ueno writes a new setting of “Strange Fruit,” the powerful song, made famous by Billie Holiday, that portrays violence against Black Americans and that, in part, led to Holiday’s prosecution by the U.S. government. It’s impossible not to imagine Holiday’s ancestral shadow as part of this work: Alongside Alma and Soonja, she becomes its third matriarch.

Press

Reviews/ARTICLES

THE WIRE

Publication

2020 December

REVIEW BY

Emily Pothast

Originally published

in Publication

(Link︎︎︎)

Ken Ueno & Reference Sine last thoughts before the global acedia Nonessential DL With its distinctive combination of amplification and distortion, the electric megaphone has an aesthetic of protest. For UC Berkeley music professor and composer Ken Ueno, the bullhorn has become an extension of his extended vocal technique, rooted in circular breathing and throat-singing techniques. On last thoughts before the global acedia, he joins forces with Flagstaff, Arizona trio Reference Sine to develop two distinct vibes for their collective improvisatory palette. The first, “On Earth”, is a cathartic clamour of glossolalic grunts, clattering percussion and frazzled electronics. “Briefly Gorgeous”, meanwhile, explores the opposite end of the dynamic range, inching its well timed scritches and judicious slurps along a backdrop of open and accommodating silence.

Press

Reviews

THE SEVENTH EDITION OF

THE BI-CITY BIENNALE SETS UP

IN SHENZHEN TO INVESTIGATE

THE URBAN VILLAGE

THE BI-CITY BIENNALE SETS UP

IN SHENZHEN TO INVESTIGATE

THE URBAN VILLAGE

Wallpaper

December 28, 2017

by Anna Yudina

Originally published

in Wallpaper

(Link︎︎︎)

Shenzhen is the place where lots of people come to reinvent their identity,’ says architect Thomas Tsang about the city which – together with its neighbour Hong Kong – hosts the Bi-City Biennale of UrbanismArchitecture, or UABB. Tsang’s own contribution – an immersive installation designed to amplify the soundwork by composer and vocalist Ken Ueno – is one of the exhibition’s highlights that mark the 2017 Biennale’s active involvement with contemporary art. The notions of identity and authenticity are central to this year’s edition of UABB. Titled ‘Cities Grow in Difference’, it celebrates the city as a ‘complex ecosystem’ and promotes urban policies that ‘acknowledge diverse values and lifestyles’ rather than imposing ‘globalised and commercialised standard configurations’ that render cities ‘homogenous and generic’.

Press

Reviews

ALBUM REVIEW:

PRISM QUARTET,

COLOR THEORY

PRISM QUARTET,

COLOR THEORY

The Log Journal

April 14, 2017

by Steve Smith

Originally published

in The Log Journal

(Link︎︎︎)

PRISM QUARTET

COLOR THEORY

(XAS, 2017)

The four members of PRISM Quartet, an award-winning ensemble based in New York City, Philadelphia, and Ann Arbor, have been singleminded in their pursuit of new sonic and stylistic frontiers for their mutual instrument of choice, the saxophone. But that’s not to suggest that Timothy McAllister, Taimur Sullivan, Matthew Levy, and Zachary Shemon have been close-minded in matters of ensemble integrity. Alongside strictly four-part inventions, PRISM has engaged in eye- and ear-opening collaborations with other artists and ensembles, including prominent jazz saxophonists such as Steve Lehman, Dave Liebman, Rudresh Mahanthappa, Greg Osby, Tim Ries, and Miguel Zenón; the ensemble Music from China; esteemed choir The Crossing; and early-music consort Piffaro.

Disparate though all these projects might be, what they all share in common is an enviable combination of integrity, individuality, and instant appeal – no mean feat, given some of the more rigorous creative modes PRISM has investigated. Those qualities are amply evident on Color Theory, issued April 14 as the second release from the quartet’s new label, XAS Records (distributed by Naxos). Without question one of PRISM’s most elaborate undertakings, the project finds the foursome working with So Percussion, another pioneering quartet devoted to breaking new ground and forging new alliances, and Partch, a West Coast percussion ensemble that focuses on the Seussian microtonal instruments created by maverick composer Harry Partch.

The common thread among the three pieces on the album – Blue Notes and Other Clashes by Steven Mackey, Future Lilacs by Ken Ueno, and Skiagrafies by Stratis Minakakis – is the notion of saxophones and percussion used as raw materials to build a new repertoire inspired by and based on the notion of musical colors. Ueno took the concept a step further, calling for the physical transformation of one of the saxophones and adding an electric guitar in altered tuning to the mix. Derek Johnson, a skillful and versatile Bang on a Can associate, handles the guitar assignment; Minakakis is also present, serving as the conductor on his own piece and Ueno’s.

...

...

Both Ueno and Minakakis opt for long spans rather than discrete segments in their works for PRISM and Partch. Ueno – whose creative span runs from solo improvisation and the rugged intricacies of Central Asian multiphonic throat-singing to rigorously constructed symphonic works and opera – found inspiration for Future Lilacs in “Futures in Lilacs,” a 2007 poem by Robert Hass sparked in turn by Walt Whitman’s iconic “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d.”

Opening with a stinging guitar note played obsessively on alternating strings to produce shifting overtones, Ueno gradually introduces the unconventional Partch instruments – “Castor” and “Pollux” canons, chromelodeon, adapted viola, cloud chamber bowls, and bass marimba – their unconventional tonal and timbral qualities at once disorienting and inviting. The saxophones make their presence known some three-plus minutes into the piece, notes bending and slurring in accord with Partch implements and roiling guitar alike. Ueno compels the PRISM players to make full use of their horns’ capacity to sputter, hiss, and clack, and further deploys what he calls a “hookah sax”: a tenor saxophone with seven feet of rubber hose inserted between its mouthpiece and body – a method made famous by the seminal New York City noise-improvisation trio Borbetomagus.

Opening with a stinging guitar note played obsessively on alternating strings to produce shifting overtones, Ueno gradually introduces the unconventional Partch instruments – “Castor” and “Pollux” canons, chromelodeon, adapted viola, cloud chamber bowls, and bass marimba – their unconventional tonal and timbral qualities at once disorienting and inviting. The saxophones make their presence known some three-plus minutes into the piece, notes bending and slurring in accord with Partch implements and roiling guitar alike. Ueno compels the PRISM players to make full use of their horns’ capacity to sputter, hiss, and clack, and further deploys what he calls a “hookah sax”: a tenor saxophone with seven feet of rubber hose inserted between its mouthpiece and body – a method made famous by the seminal New York City noise-improvisation trio Borbetomagus.

Like much of Harry Partch’s music as well as certain Asian traditions that have informed Ueno’s compositional style, Future Lilacs has a ceremonial quality, its players sounding fitfully as if ordained by ritual. Rollicking and meditative in alternation, the music sustains its initial fascination; Ueno’s techniques are novel, but never mere novelty, serving expressive purposes consistently throughout this haunting work.

CORRECTION (APR. 19, 2017): A previous version of this review listed the diamond marimba and kithara among the Harry Partch instruments used for Ken Ueno’s composition Future Lilacs. Those instruments are included on the album, but are not featured in Ueno’s piece.

Press

Reviews

A Composer Plays

with Space, Time,

and Culture

with Space, Time,

and Culture

Seen and Hear International

April 21, 2017

by Daniele Sahr

Originally published in

Seen and Heard International

(Link︎︎︎)

UNITED STATES

KEN UENO

Majel Connery (vocalist),

Flux Quartet,

Opera Cabal.

National Sawdust,

Brooklyn.

7.4.2017. (DS)

Ken Ueno - Aeolus

(NY Premiere)

KEN UENO

Majel Connery (vocalist),

Flux Quartet,

Opera Cabal.

National Sawdust,

Brooklyn.

7.4.2017. (DS)

Ken Ueno - Aeolus

(NY Premiere)

It was hard to tell where the sound was coming from or even what it was – dark, hollow, perhaps recorded, perhaps electronic. Turning to look behind the seated audience at National Sawdust in Brooklyn, I saw that it was coming directly from composer Ken Ueno, decked out in a black medieval-inspired robe-meets-spacesuit cloak, and holding a white megaphone to his mouth. As he walked around, he was filling the space with one of his signature sonic skills – this time, sonar clicking – that spread a wooden quality of reverb throughout the whole room. The Flux Quartet sat on stage in front of a video screen, meditatively waiting, between two unmanned standing microphones.

This was the beginning of Ueno’s new opera Aeolus, taking its name from the Greek mythological keeper of the winds. Vocalist Majel Connery of Chicago-based Opera Cabal would soon come to stand at one of the microphones – the other would always stand unused, abandoned. In a deep alto pop-oriented drone, that seemed to connect directly from her jaw to her ribs, she sang, “Myths,” becoming the futuristic chanteuse of this time-warping mythical opera.

Odysseus is a force, a character throughout this 90-minute journey, but he is never outright mentioned. Instead, his angst flows in a first-person narrative, through Connery’s vocals or Ueno’s voiceover poetic verse: “The winds that keep me from Ithaca are my own,” he proclaims. His journey might symbolize that which lives in all of us – yearning to connect yet only finding ourselves to blame for the isolation that abounds. As one pre-recorded phrase so poignantly delivers, with its mantel of self-reflective contemporary black humor, “I have no way of navigating between the silence of your texts.”

In his adept handling of all media, Ueno mixes every component of this work with finesse. Aeolus offers a balance between mesmerizing images of seascapes and dunes set to voice-over with quartet accompaniment. When electronically derived club-culture bass enters the soundscape, it’s as pointed as the textured string tones that intertwine with vocals. Midway, Ueno comes out in front of the stage to speak (not sing) rhythmically in a surreal mixture of lecture and pseudo-comedy routine, using his iPhone to command the beginning and end of pre-recorded percussion samples. It resembled an alien imitating a human stand-up routine with misfired drumming joke punctuations. Perhaps a take on the challenges of modern-day overcommunication – that leads to miscommunication.

As a composer, Ueno plays with the boundaries of space, time, and culture. These components create a unique three-dimensional effect that he laces together with musical techniques. While he calls Aeolus an opera, it could very well be a living sculpture or a poetic collage. Within this eclectic space of exploration (which includes throat singing) he produces songs like There is No One Like You sung by Connery, that you want to add to your soundtrack to reshuffle an evening after work. It is not only testament to his accessibility but also his wide range of musicality that he can touch the tastes of all his listeners.

Press

ARTICLES

SOUNDS & MUSIC:

COMPOSER AND VOCALIST

BRINGS AMALGAM OF

STYLES TO PITTSBURGH

RESIDENCY

COMPOSER AND VOCALIST

BRINGS AMALGAM OF

STYLES TO PITTSBURGH

RESIDENCY

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

November 8, 2015

by Elisabeth Bloom

Originally published

in Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

(Link︎︎︎)

(PHOTO: BILL WADE/

POST GAZETTE)

POST GAZETTE)

Swaying back and forth, his right foot in front of his left, Ken Ueno stared off into the distance, nearly catatonic, as if primed for a fight.

But this was no boxing ring, and Mr. Ueno, a composer and vocalist, had no opponent.

Rather, it was a concert of experimental improvisation and chamber music presented by Alia Musica Pittsburgh in July. It marked the first performance of Mr. Ueno’s yearlong residency with the new music organization. Ken Ueno, is a composer,vocalist sound artist whose music draws from several inspirations — from Tuvan throat singing to heavy metal.

But this was no boxing ring, and Mr. Ueno, a composer and vocalist, had no opponent.

Rather, it was a concert of experimental improvisation and chamber music presented by Alia Musica Pittsburgh in July. It marked the first performance of Mr. Ueno’s yearlong residency with the new music organization. Ken Ueno, is a composer,vocalist sound artist whose music draws from several inspirations — from Tuvan throat singing to heavy metal.

Nearly everything about this concert was weird. It took place in a living room in Lawrenceville. Admission was $5. The opening act was an improvised music band whose members included a shirtless man wearing a skull mask. The space, with off-white walls, lacy curtains, modest chandelier and anachronistic artwork, made for an unusual environment in which to experience music. Perhaps that was the point.

Mr. Ueno, 45, was educated at West Point, Harvard, Yale, Boston University and the Berklee College of Music, and is on the faculty of the University of California, Berkeley. Some of the premier new music groups in the country, including eighth blackbird and the Boston Modern Orchestra Project, have performed his works, and he has a spot in The Grove Dictionary of American Music. What could someone with this pedigree think of this concert in a Lawrenceville living room?

Mr. Ueno, 45, was educated at West Point, Harvard, Yale, Boston University and the Berklee College of Music, and is on the faculty of the University of California, Berkeley. Some of the premier new music groups in the country, including eighth blackbird and the Boston Modern Orchestra Project, have performed his works, and he has a spot in The Grove Dictionary of American Music. What could someone with this pedigree think of this concert in a Lawrenceville living room?

It became clear that he not only was comfortable with the strange circumstances, he seemed to welcome them. That pre-performance trance showed it.

“I guess, in that case, I was trying to prep the audience,” he said later, during an interview at a Highland Park café. “I feed off the intensity of listening.”

For him to be in the zone, his audience needed to be in the zone, too.

“I guess, in that case, I was trying to prep the audience,” he said later, during an interview at a Highland Park café. “I feed off the intensity of listening.”

For him to be in the zone, his audience needed to be in the zone, too.

His performance opened with a loud, shocking scream. Over the course of his solo improvisation (he later performed with two musicians playing bass and electronics), he produced an eclectic series of sounds: clicks, like quick water drops in a ceramic bathtub; thumping heartbeats; heavy breaths; television static, jarring and surprising. You could feel it in the ground, and, listening to him, you sympathized with your own vocal cords. (“It doesn’t hurt,” he claimed.)

He also used a megaphone, which allowed him to experiment with physical space and with the prop’s own sonic qualities. With his knees on the floor, he placed it on the ground and drilled muffled vocals through it, or he pulled it away to his side, creating, as he later put it, a counterpoint of sorts between voice and body.

When he finished, a man sitting in the living room gasped, “Wow.”

Mr. Ueno’s music is challenging. It is not for the faint of heart, nor for people who cringe at the thought of hearing contemporary music of any sort in the traditional concert hall. That is something the composer acknowledges. “I know people are going to think it’s weird,” he said.

When he finished, a man sitting in the living room gasped, “Wow.”

Mr. Ueno’s music is challenging. It is not for the faint of heart, nor for people who cringe at the thought of hearing contemporary music of any sort in the traditional concert hall. That is something the composer acknowledges. “I know people are going to think it’s weird,” he said.

But watching and hearing him perform in that living room was ear-opening, too. On the one hand, his music toes the fringe of modern musical culture. On the other, his success — as he puts it, “I am lucky enough to be able to live from what I do” — suggests there’s something to it.

The second chapter of Mr. Ueno’s residency takes place Thursday at First Unitarian Church in Pittsburgh, when he joins the Alia Musica orchestra for a performance of his vocal concerto, “On a Sufficient Condition for the Existence of Most Specific Hypothesis.” Mr. Ueno will give a lecture about the work prior to the performance. The program also features a piece by Federico Garcia-De Castro, Alia Musica’s artistic director, who met Mr. Ueno during a composition festival in Thailand.

The second chapter of Mr. Ueno’s residency takes place Thursday at First Unitarian Church in Pittsburgh, when he joins the Alia Musica orchestra for a performance of his vocal concerto, “On a Sufficient Condition for the Existence of Most Specific Hypothesis.” Mr. Ueno will give a lecture about the work prior to the performance. The program also features a piece by Federico Garcia-De Castro, Alia Musica’s artistic director, who met Mr. Ueno during a composition festival in Thailand.

A self-taught vocalist, Mr. Ueno draws on various extended techniques and inspirations: the sub-tones and screams common in heavy metal, throat singing traditions from around the world, multiphonics (producing multiple notes at once), overtones, circular breathing and the ability to sing at an extremely high register — up to a C-Sharp three octaves above middle C. Much of this music is what we might consider wordless; it traverses “the gray area between language and non-language,” he said.

While he often improvises (including during the cadenza of the vocal concerto), he also uses traditional Western notation and his own notation, supplementing it with video when necessary.

While he often improvises (including during the cadenza of the vocal concerto), he also uses traditional Western notation and his own notation, supplementing it with video when necessary.

There are throat-singing traditions all over the world — including in Inuit, South African, Tuvan and Sardinian cultures — yet Mr. Ueno’s music is not an anthropological study.

“I know he has done the research about vocal extended techniques from around the world,” Mr. Garcia-De Castro said. “He’s not using them in a pure sense. He’s not doing a tribute to these traditions. He’s just incorporating them as things to work with.”

“I know he has done the research about vocal extended techniques from around the world,” Mr. Garcia-De Castro said. “He’s not using them in a pure sense. He’s not doing a tribute to these traditions. He’s just incorporating them as things to work with.”

Mr. Ueno’s other influences are catholic: Bela Bartok, John Coltrane, B.B. King, Metallica and, above all, Jimi Hendrix.“I am a musician because of Jimi Hendrix,” he said. “I was always much more into academics and sports than music, until I started to play electric guitar.”

That happened in earnest after he sustained an injury while in college at West Point. During his recovery, he wrote songs and practiced his instrument eight or nine hours a day. He still needed to finish his bachelor’s degree, so he decided to study at the Berklee College of Music, where he encountered Bartok’s String Quartet No. 4 for the first time.

That happened in earnest after he sustained an injury while in college at West Point. During his recovery, he wrote songs and practiced his instrument eight or nine hours a day. He still needed to finish his bachelor’s degree, so he decided to study at the Berklee College of Music, where he encountered Bartok’s String Quartet No. 4 for the first time.

“I felt like my body understood the music, because it was like heavy metal. It was like a heavy metal string quartet,” he said. But he recognized there were more complex underpinnings to that visceral response. He wanted to figure them out, so he decided to compose.

Mr. Ueno’s Pittsburgh residency is supported by a $35,000 grant from the Pittsburgh Foundation and the Heinz Endowments, which also funds the composition of a new work for Alia Musica. The endeavor illuminates how Alia Musica, which was founded eight years ago, is becoming clearer in its purpose and growing in its impact.

Mr. Ueno’s Pittsburgh residency is supported by a $35,000 grant from the Pittsburgh Foundation and the Heinz Endowments, which also funds the composition of a new work for Alia Musica. The endeavor illuminates how Alia Musica, which was founded eight years ago, is becoming clearer in its purpose and growing in its impact.

In 2014, the group produced an ambitious festival of new music that included a recital with prominent composer-pianist Frederic Rzewski. Over the past few years, its musicians have performed across the Midwest and East Coast, and in June, it was a resident ensemble at a music festival in Panama.

This project with Mr. Ueno reflects the organization’s efforts to create distinctive experiences around new music — concerts that are relevant to audience members, that they are unlikely to forget.

This project with Mr. Ueno reflects the organization’s efforts to create distinctive experiences around new music — concerts that are relevant to audience members, that they are unlikely to forget.

The composer will visit Pittsburgh several times over the course of the year to become familiar with the area and the musicians who will premiere his work in the spring. This knowledge will inform his composition of the new piece. Over the summer, he was a proper tourist: He visited Fallingwater and Kentuck Knob, went to a Pirates game, attended local concerts and explored restaurants in the city. Next Sunday’s Steelers game is on the itinerary for this visit.

He refers to this process as a “person-specific” approach to composition, the notion that music can be fitted to a place and to its performers much like a custom-made suit.

“I’ve also been using a metaphor of going to a three-star Michelin restaurant,” he said. “You go that place essentially to make a little pilgrimage. There’s something special about that chef, that place.”

He refers to this process as a “person-specific” approach to composition, the notion that music can be fitted to a place and to its performers much like a custom-made suit.

“I’ve also been using a metaphor of going to a three-star Michelin restaurant,” he said. “You go that place essentially to make a little pilgrimage. There’s something special about that chef, that place.”

Ultimately, it gives added importance to hearing the music in the flesh, something that is vital for Mr. Ueno and Alia Musica. The connection between creator, performer and audience is critical to the experience of listening to some of his favorite artists, and he is aiming to translate that to the classical music world.

“Listening to the Jimi Hendrixes and the Coltranes of the world, I was inspired by the fact that they extended the history of their instruments, and in my own little way, I’m interested in extending my own vocal practice,” he said.

“Listening to the Jimi Hendrixes and the Coltranes of the world, I was inspired by the fact that they extended the history of their instruments, and in my own little way, I’m interested in extending my own vocal practice,” he said.

ELIZABETH BLOOM: ebloom@post-gazette.com or 412-263-1750.

Twitter: @BloomPG.

Twitter: @BloomPG.

Press

ARTICLES

KEN UENO -

VISIBLE REMINDER OF

INVISIBLE LIGHT

VISIBLE REMINDER OF

INVISIBLE LIGHT

hocTok.com

September 14, 2015

by Doriana S. Molla

Originally published

in hocTok.com

(Link︎︎︎)

DORIANA S. MOLLA:

I pulse, when you breathe (2008), is a piece of music written by Ken Ueno for amplified soprano and alto flute.

The composer elaborates, “This piece is a song in search of the main melody, a setting of the short text. Throughout much of the piece, the sounds of the text are gradually discovered, through divergences, parries, continuations, and, finally, a short glimpse, which turns out to be a sort of arrival.”

All of it sounds like a dream sequence and a metaphor for life at the same time. Poetry. What flickering light did Ken Ueno follow to jot down the notes and words for this work?

I pulse, when you breathe (2008), is a piece of music written by Ken Ueno for amplified soprano and alto flute.

The composer elaborates, “This piece is a song in search of the main melody, a setting of the short text. Throughout much of the piece, the sounds of the text are gradually discovered, through divergences, parries, continuations, and, finally, a short glimpse, which turns out to be a sort of arrival.”

All of it sounds like a dream sequence and a metaphor for life at the same time. Poetry. What flickering light did Ken Ueno follow to jot down the notes and words for this work?

KEN UENO:

I started with a poem I wrote in Japanese – “this wind, the resonance of song through the trees.”

I like that Japanese consists of mainly pure vowels and that there are fewer words than in English. Endemically, then, there are opportunities for sounds to evoke other potential meanings, or stand isolated as pure sounds. To frame the transition between semantic and non-semantic signification of vocal sounds, I orchestrated the breath and timbre around the phonemes of the poem.

In terms of light and the sense of wonder and the presences of the present moment that light makes evident, I have been inspired by what I call “secret meridians.” (Here’s a short video: Link︎︎︎). I like Turrell and T.S. Eliot too (“visible reminder of invisible light,” e.g.).

I started with a poem I wrote in Japanese – “this wind, the resonance of song through the trees.”

I like that Japanese consists of mainly pure vowels and that there are fewer words than in English. Endemically, then, there are opportunities for sounds to evoke other potential meanings, or stand isolated as pure sounds. To frame the transition between semantic and non-semantic signification of vocal sounds, I orchestrated the breath and timbre around the phonemes of the poem.

In terms of light and the sense of wonder and the presences of the present moment that light makes evident, I have been inspired by what I call “secret meridians.” (Here’s a short video: Link︎︎︎). I like Turrell and T.S. Eliot too (“visible reminder of invisible light,” e.g.).

DSM:

whatWALL? (2003) for alto saxophone and quadraphonic tape. There is so much to experience/learn from this amazing piece. At the very end of the program notes for it, we read, “‘whatWALL?’ is also a personal call to arms, that an artist should always strive to go beyond whatever boundaries stand before him.”

What are the harshest boundaries you have surpassed to achieve the level of confidence and level of superb artistry?

whatWALL? (2003) for alto saxophone and quadraphonic tape. There is so much to experience/learn from this amazing piece. At the very end of the program notes for it, we read, “‘whatWALL?’ is also a personal call to arms, that an artist should always strive to go beyond whatever boundaries stand before him.”

What are the harshest boundaries you have surpassed to achieve the level of confidence and level of superb artistry?

KU:

The biggest boundary for an artist is the best that he/she has already achieved. Most of the time, we are living in the past. Even what we normally consider as the present is a latency. Creative endeavor, as acts of faith, are especially potent as mechanisms that give us agency to change the future.

Composing a 20-min work takes months and requires planning and coordination with a team of people (administrators, vendors, the ensemble, the audience).

Each time we take that leap of faith into the future, whatever our realm of creative endeavor might be, taking contingent risks, even if the project itself fails, we are emboldened for having taken that risk, and our aura expands. It is in that space of growth that I might mark my own progress in having lived. It also becomes the wall, a new marker that drives me to go further.

Art is an attitude, at once a way of seeing (and in my case hearing) the world and imaging what one might see (hear) that fills us daily and challenges us to the end of our days.

The biggest boundary for an artist is the best that he/she has already achieved. Most of the time, we are living in the past. Even what we normally consider as the present is a latency. Creative endeavor, as acts of faith, are especially potent as mechanisms that give us agency to change the future.

Composing a 20-min work takes months and requires planning and coordination with a team of people (administrators, vendors, the ensemble, the audience).

Each time we take that leap of faith into the future, whatever our realm of creative endeavor might be, taking contingent risks, even if the project itself fails, we are emboldened for having taken that risk, and our aura expands. It is in that space of growth that I might mark my own progress in having lived. It also becomes the wall, a new marker that drives me to go further.

Art is an attitude, at once a way of seeing (and in my case hearing) the world and imaging what one might see (hear) that fills us daily and challenges us to the end of our days.

DSM:

Listening to your music, reading the program notes, listening/reading about your opinions compares to a thrilling mental speedrace: all the places, the names, timelines, zones, landscapes. You’re not even bragging. You invite/dare anyone to join you on your joy ride or find one’s own. Who inspired you to be so generous with your own knowledge?

Listening to your music, reading the program notes, listening/reading about your opinions compares to a thrilling mental speedrace: all the places, the names, timelines, zones, landscapes. You’re not even bragging. You invite/dare anyone to join you on your joy ride or find one’s own. Who inspired you to be so generous with your own knowledge?

KU:

I have so many heroes. Jimi Hendrix and John Coltrane. James Joyce, Samuel Beckett, Italo Calvino, Garcia Marquez, are other heroes. James Turrell, Agnes Martin, Gerhard Richter.

One of the first things art does is curate empathy. In my own work, I am trying to deliver in some measure what I have received from my favorite art. Art first has to be good and earnest. Then, it can reach almost anybody. I think that many programmers are afraid that their audiences can’t get challenging art. What that means is that they don’t believe in the art and that they don’t trust their audiences. One of my biggest inspirations in terms of that earnestness and generosity is Robert F. Kennedy’s speech on the death of Martin Luther King. When he was campaigning for the presidency in 1968, just months before his own assassination, he landed in Indianapolis to address a largely African-American audience. Shortly before he arrived, he received word that MLK had been assassinated and it was up to him to inform the crowd. After he broke the news, he reminded them that he had also lost someone important to him and that he, too, was killed by a white man. Then, he did the most startling thing; he shared with the audience a favorite piece of poetry that had comforted through such hard times. It was a selection from Aeschylus’ Agamemnon. Isn’t that kind of extraordinary? A Harvard-educated, rich, white man addressing an African-American working-class crowd quoting Aeschylus? The poem is, indeed, quite moving, but what I think really worked was that Robert Kennedy did not second-guess his audience’s capacity to get it; he shared what was earnest to him. That honesty itself translates. The efficacy of that moment is one of reasons why in the following weeks after that day, Indianapolis did not go up in flames with riots, as did much of the rest of the country. So, that’s what I try to do.

I seek out art that has the power to sooth my soul and try to deliver that to my audience. I trust that whatever might move me, might also move others.

I have so many heroes. Jimi Hendrix and John Coltrane. James Joyce, Samuel Beckett, Italo Calvino, Garcia Marquez, are other heroes. James Turrell, Agnes Martin, Gerhard Richter.

One of the first things art does is curate empathy. In my own work, I am trying to deliver in some measure what I have received from my favorite art. Art first has to be good and earnest. Then, it can reach almost anybody. I think that many programmers are afraid that their audiences can’t get challenging art. What that means is that they don’t believe in the art and that they don’t trust their audiences. One of my biggest inspirations in terms of that earnestness and generosity is Robert F. Kennedy’s speech on the death of Martin Luther King. When he was campaigning for the presidency in 1968, just months before his own assassination, he landed in Indianapolis to address a largely African-American audience. Shortly before he arrived, he received word that MLK had been assassinated and it was up to him to inform the crowd. After he broke the news, he reminded them that he had also lost someone important to him and that he, too, was killed by a white man. Then, he did the most startling thing; he shared with the audience a favorite piece of poetry that had comforted through such hard times. It was a selection from Aeschylus’ Agamemnon. Isn’t that kind of extraordinary? A Harvard-educated, rich, white man addressing an African-American working-class crowd quoting Aeschylus? The poem is, indeed, quite moving, but what I think really worked was that Robert Kennedy did not second-guess his audience’s capacity to get it; he shared what was earnest to him. That honesty itself translates. The efficacy of that moment is one of reasons why in the following weeks after that day, Indianapolis did not go up in flames with riots, as did much of the rest of the country. So, that’s what I try to do.

I seek out art that has the power to sooth my soul and try to deliver that to my audience. I trust that whatever might move me, might also move others.

DSM:

All moments stop here and together we become every memory that has ever been (2003).

In our daily struggle to maintain our identity in a post-industrial digital world, we are all music boxes, analog songs seeking a space in which to be heard. Are there any magic key words guiding us to finding that space, all us ‘analog songs’ seek?

All moments stop here and together we become every memory that has ever been (2003).

In our daily struggle to maintain our identity in a post-industrial digital world, we are all music boxes, analog songs seeking a space in which to be heard. Are there any magic key words guiding us to finding that space, all us ‘analog songs’ seek?

KU:

In my music, I am seeking to privilege the live experience. Years ago, I remember going to the Guggenheim Bilbao where I saw a room full of black paintings. I stayed there for about an hour. After a while, it occurred to me that these paintings defy mechanical representation – these paintings are not the ones that are on calendars and t-shirts in the gift shop.

Further, over the course of the time I spent there, I noticed that horizontal bands that marked the Franz Klines were subtly different shades of black. The Robert Motherwells were articulated by complex brushstrokes. These paintings said to me that I had to stand in front of them. That I had to make the pilgrimage to experience them live, that that live experience could not be substituted. By extension, it was saying that my individual life mattered.

Person-specific music demands that it be experienced by specific people performing it. In the face of the ever-increasing digitization of our lives, I am questioning the transportability of classical music. “Analog songs” is a metaphor for the uniqueness in all of us that makes us human. I want to help people realize their “analog songs” and have the courage to actualize themselves.

In my music, I am seeking to privilege the live experience. Years ago, I remember going to the Guggenheim Bilbao where I saw a room full of black paintings. I stayed there for about an hour. After a while, it occurred to me that these paintings defy mechanical representation – these paintings are not the ones that are on calendars and t-shirts in the gift shop.

Further, over the course of the time I spent there, I noticed that horizontal bands that marked the Franz Klines were subtly different shades of black. The Robert Motherwells were articulated by complex brushstrokes. These paintings said to me that I had to stand in front of them. That I had to make the pilgrimage to experience them live, that that live experience could not be substituted. By extension, it was saying that my individual life mattered.

Person-specific music demands that it be experienced by specific people performing it. In the face of the ever-increasing digitization of our lives, I am questioning the transportability of classical music. “Analog songs” is a metaphor for the uniqueness in all of us that makes us human. I want to help people realize their “analog songs” and have the courage to actualize themselves.

DSM:

Very assertive definition of self is of utmost importance especially for artists/composers who share their thoughts and feelings with the rest of the world open to all kinds of critiques by professionals and amateurs alike. You’ve said, “I am a multiplicity of identities, maybe unresolved. And maybe one possible contemporary proposition is that it doesn’t have to be a resolved linearity.” Did you always have this clarity about your own definition of self? What helped you reach this conclusion and is it finalized?

Very assertive definition of self is of utmost importance especially for artists/composers who share their thoughts and feelings with the rest of the world open to all kinds of critiques by professionals and amateurs alike. You’ve said, “I am a multiplicity of identities, maybe unresolved. And maybe one possible contemporary proposition is that it doesn’t have to be a resolved linearity.” Did you always have this clarity about your own definition of self? What helped you reach this conclusion and is it finalized?

KU:

It took me years to think of myself as a manifold and be comfortable with it. My formative years were complex – I was born in New York, but my family moved a number of times internationally. By the time we settled in Los Angeles, when I was seven, I spoke English with a British accent and didn’t feel American. In fact, I’ve always felt like an outsider – still do.

As a sensitive youth, I remember feeling the pressure to conform. This troubled me enough that it was a major factor in my decision to go to West Point. I thought that if I served my country, then I could prove that I am American. That turned out to be naive and misplaced.

One of the benefits of a life in art has been that I have come to terms with my weirdness. The truth is, we are all many things. Contemporary identity is more like Internet channels – we are meta-beings. Hegelian summation is a 19th century, nationalist, non-cosmopolitan construct and outdated.

It took me years to think of myself as a manifold and be comfortable with it. My formative years were complex – I was born in New York, but my family moved a number of times internationally. By the time we settled in Los Angeles, when I was seven, I spoke English with a British accent and didn’t feel American. In fact, I’ve always felt like an outsider – still do.

As a sensitive youth, I remember feeling the pressure to conform. This troubled me enough that it was a major factor in my decision to go to West Point. I thought that if I served my country, then I could prove that I am American. That turned out to be naive and misplaced.

One of the benefits of a life in art has been that I have come to terms with my weirdness. The truth is, we are all many things. Contemporary identity is more like Internet channels – we are meta-beings. Hegelian summation is a 19th century, nationalist, non-cosmopolitan construct and outdated.

DSM:

A composer, performer, sound artist, professor, and overall explorer of all things dealing with the inner workings of mind and soul. What are the constants in your life encouraging and moving you to keep up with your own set pace?

A composer, performer, sound artist, professor, and overall explorer of all things dealing with the inner workings of mind and soul. What are the constants in your life encouraging and moving you to keep up with your own set pace?

KU:

Art is an attitude. Art takes courage every day, as life does too. Calvino says that the world is inferno, so, “seek and learn to recognize who and what, in the midst of inferno, are not inferno, then make them endure, give them space.”